One moment, I’m gliding through serene waterways in the Térraba-Sierpe mangroves, scanning the bank for camouflaged caimans and crocodiles. It’s tranquil and quiet. The only sounds breaking the silence are the buzz of insects, the gentle rustle of branches as capuchin monkeys leap from tree to tree, and the sharp call of the fiery-billed aracari flashing past in hues of color.

In this moment, I’m fully immersed in nature, a newly enthusiastic birdwatcher armed with my bird call app, ready to capture any glittering feathered friend. Finding a unique toucan species become my obsession on this trip.

Suddenly, things take a turn. My head is between my knees, struggling against nausea. We’ve left the serene mangroves and are now navigating the ocean’s mouth, the same little boat that deftly maneuvered narrow channels now conquering massive waves.

As our boat rounds the bend of the peninsula’s western edge, we stop to admire a pair of sea turtles in the act of mating. Above the water, the treetop bungalows where we’ll spend the night come into view.‘Welcome to our office,’ comments our guide, Tibisay.

This adventurous journey consists of multiple stages, from a tiny plane ride from San Jose, Costa Rica’s capital, to Palma Sur airport, flying over lush mountains and the iconic whale tail beach, to now standing on the golden sands of secluded San Pedrillo beach. Our final trip to the Corcovado Wilderness Lodge involves a tractor, dubbed the ‘jungle limo’, that bravely tackles the steep hills of the reserve to usher us to our destination.

Proving that great experiences often require effort, Corcovado Wilderness Lodge is located at the edge of Corcovado National Park, celebrated for being the most ecologically diverse area on the planet. This remarkable region recently marked its 50th anniversary, having been designated a national park back in 1975. This year, the Osa Peninsula has made it to numerous travel lists, from BBC to Telegraph and the New York Times. This stunning location has consistently ranked among the world’s most underrated destinations by Time Out.

Although there are newly established direct flights from San Jose to airstrips on the peninsula, including Puerto Jiménez and Drake Bay, Corcovado National Park strictly limits the number of visitors to safeguard its delicate ecosystems. Each visitor must be accompanied by a certified guide, and park rangers are on site to check for prohibited plastic items.

Our insightful and observant guide, Tibisay, is a resident of Limón, situated along the Caribbean coast. On the San Pedrillo trail, which unexpectedly combines coastal vistas and rainforest, she guides us through the lush environment, pointing out strangler figs and the gnarled roots of a 250-year-old garlic tree. We follow the prints of a rare tapir, with about 200 of these elusive creatures residing in the park. Before long, we spot one foraging on jobo fruit, discarded by spider monkeys.

As we advance through this vibrant landscape, we encounter scarlet macaws, crocodiles, and coatis at play. The trek culminates with Tibisay’s discovery of a sloth leisurely hanging from a tree, its fur slightly damp from earlier rain.

I visited in August, during a peak wildlife observation period. While many tourists label this as the rainy season, locals affectionately refer to it as the green season. This is the time to witness humpback whales breaching the water, a sight I had my first taste of near Isla del Cano, albeit interrupted by a rogue bout of seasickness. Thankfully, just days later, I enjoyed an uninterrupted view while swimming at sunrise in the tranquil waters of Golfo Dulce.

Despite typically being an early riser, my howler monkey alarm clock effectively pulls me to the beach. The surrounding area at the eco-boutique Kunken Lodge is buzzing with wildlife, including the extremely venomous fer-de-lance viper, a source of excitement for our wildlife-hungry tour guide and sheer terror for the rest of us. Conditions are perfect for swimming; the sand feels plush and the water is just right. As I swim towards a lone heron perched on a post, I suddenly spot two humps, one slightly larger, drifting just beneath the surface.

During this season, humpback whales take refuge in Golfo Dulce to nurture their young. Over several days spent sailing and swimming in this serene gulf, we spot multiple mother-and-calf pairs surfacing together. Golfo Dulce offers breathtaking marine experiences with stingrays skimming across the seafloor and vibrant schools of snapper dancing among shipwrecks.

Although a few resorts can be spotted along its shores, this expansive stretch of water and rainforest remains blissfully untouched. The eastern coastline is enveloped by Piedras Blancas National Park, one of the latest and least explored parks in Costa Rica. After an invigorating snorkeling session, we bare our sandy feet on an empty beach bordering the national park, walking for 20 minutes until we arrive at Dolphin Quest, a cozy eco-homestay run by brothers Jahza and Reymar, along with their father, Reymundo.

Our lunch at Dolphin Quest features a delightful array of plantain, coconut ceviche, and vibrant salads; everything entirely vegan and sourced from the area. Led by on-site nutritionist Isabella, we indulge in gut-cleansing shots of turmeric, noni, and kombucha, washed down with sugarcane, coconut, and starfruit dipped in salt. We stroll around the grounds, sampling katuk leaves straight from the branch, while Isabella enlightens us on the health benefits embedded in the local plants.

‘Look,’ she says, squeezing the spongy red head of a pinecone-shaped plant that oozes ginger-like liquid. ‘This can be utilized as shampoo.’

Once an ayahuasca retreat, Dolphin Quest evolves into a mini-ecosystem of cooperative living. In this isolated area, the balance between tourism and conservation is a tightrope walk. Piedras Blancas became a protected park due to local efforts, aiming to preserve it from logging and foster economic opportunities through tourism. ‘We support economic growth, but our resources need safeguarding first,’ Reymar states.

This philosophy is what resonates with nearly everyone we meet throughout the week, from business owners to tourism representatives to locals. When a destination suddenly attracts attention, as the Osa Peninsula may with its newfound media spotlight, managing visitor flow is crucial. This region’s strength lies in its remoteness.

More than a quarter of Costa Rica is designated as protected land, limiting infrastructure development. Only the bold, equipped with a 4X4, can navigate the treacherous, uneven roads leading from Golfo Dulce’s northeastern edge. Our skilled driver transports us through the winding roads up to Cielo Lodge, resonating with the rattles of stones and potholes. Occasionally, smooth patches break the monotony, signaling the emerging readiness of the area for tourism.

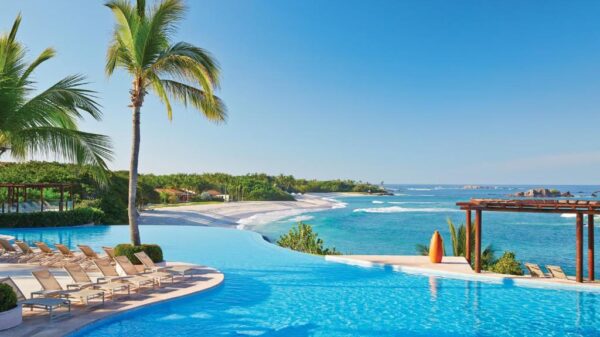

A relatively new establishment, opened by California couple Keith and Nicole Goldstein in early 2021, Cielo Lodge presents a luxurious alternative to the community-focused Dolphin Quest. This eco-luxury retreat features only six private villas nestled in the rainforest, complete with a breathtaking infinity pool overlooking the bay.

Guests enjoy intimate three-course meals next to the pool while sipping handcrafted cocktails at the bar as they watch toucans fly by. Each morning, local coffee arrives at your door to be savored from the comfort of a hammock, occasionally watched by curious squirrel monkeys. It truly embodies the dream of a perfect getaway.

In our final days in Costa Rica, we are joined by Juan Carlos from the Coto Brus tourism office along with Henry from the local tour company Surtrips. Together, they lead us on a tour through Coto Brus, a lesser-visited inland area in Costa Rica’s mountainous south, bordering Panama.

In their SUVs, we navigate steep, winding country roads to reach El Escarbadero, a family-run farm and ranch, where Toño Arrieta and his family have opened up a variety of rural experiences for visitors. Perhaps the highlight of our trip unfolds here, where we ride horses through breathtaking valleys only to find ourselves climbing up a waterfall.

The heart of this canton is San Vito, a mountain town formed by Italian immigrants in the 1950s. The cultural fusion is fascinating, with Italian influences evident everywhere, from flags fluttering above streets to a library filled with Italian literature in the town hall; however, most of the conversation is in Spanish, especially among the younger generation. An unfinished Roman arch stands sentinel in the town square, and Juan Carlos, who has roots in the area, mentions that plans are in motion to build an Italian-style boulevard.

Our visit coincides with a significant annual event for this young community: the town fair. There are bingo games, rodeo rides, stalls with local crafts, and coffee beans from nearby plantations. Juan Carlos’s wife is cooking pizzas, and the atmosphere is vibrant and lively. It’s heartwarming, evoking a protective instinct against the advancing tide of mass tourism that endangers so many emerging destinations.

Curious about the future of tourism in this region, I approach Juan Carlos, who has witnessed the town’s development throughout its duration. ‘Our vision is unique,’ he explains. ‘We aim to grow while respecting our environment and communities.’

Still, during a drive to La Amistad National Park, a transboundary protected area managed jointly by Costa Rica and Panama, Juan Carlos points out houses purchased by foreigners, sharing concerns over rising prices for locals. Nevertheless, both Juan Carlos and Henry display infectious enthusiasm and pride in showcasing their corner of Costa Rica.

We explore parks and botanical gardens, marveling at the prowess of Jason, a master birdwatcher capable of mimicking any bird call. Our itinerary includes visits to coffee farms, ranches in the mountains, bakeries, and grocery stores in town. As we leave via another small plane from an airstrip near San Vito, families gather to watch the takeoff, with children filming on their phones.

With a clear strategy surrounding tourism management that emphasizes community involvement, conservation, and environmental education, Coto Brus and the Osa Peninsula are well-positioned for welcoming international visitors. This region is far removed from the well-trodden tourist routes in northern Costa Rica, offering a genuine experience of ‘pura vida’, the country’s essence of ‘pure life,’ accessible right here in the authentic mountain community of San Vito.